Regardless of the framework, the focus should be the broad types of cooperation and their key features.

Image Source: Pexels

There are different frameworks for organising cooperation options, but those frameworks share many similarities

There are different frameworks for categorising regulatory cooperation options, each with slightly different organising principles. This includes frameworks developed by the OECD, individual economies, such as New Zealand, and various academics.

The organising principles used include the degree of formality or informality involved, the outcomes sought, or the types of mechanisms used. Many approaches use a combination of organising principles across a spectrum.

There are different ways to categorise IRC approaches

There are different ways to think about or characterise International Regulatory Cooperation (IRC) , depending on the organising principles that are used.

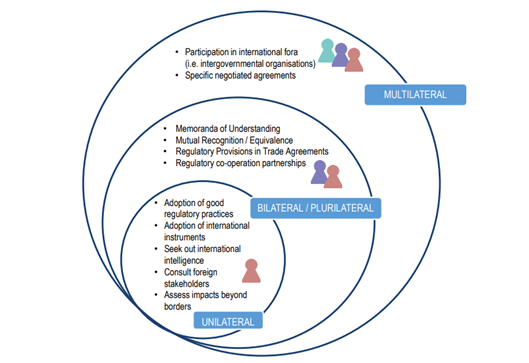

The OECD has developed several typologies or ways to categorise IRC approaches. In its 2013 keynote report International Regulatory Cooperation: Global Challenges, the OECD identified 11 different forms of IRC. In its more recent Best Practice Principles on International Regulatory Cooperation (BPP), the OECD sets out a continuum of mechanisms that can complement each other, rather than being mutually exclusive. The BPP differentiates IRC approaches into unilateral, bilateral and plurilateral, and multilateral (the latter involving international organisations).

Image Source: OECD IRC Toolkit

Image Source: Home | IRC Toolkit (mbie.govt.nz)

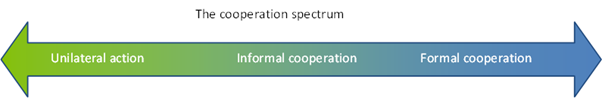

New Zealand, on the other hand, has developed a cooperation spectrum, drawing on its experience of cooperating with Australia. The spectrum moves from unilateral action at one end, through informal/soft cooperation to full harmonisation, including through shared institutions, at the other. New Zealand has shared the spectrum within APEC fora and has now developed a toolkit that explains different points on the spectrum and their respective advantages and disadvantages.

Both the OECD and New Zealand approaches note that it is possible to use different mechanisms or a combination of them, depending on the circumstances of the particular case. It is also possible to start at the softer end of the New Zealand spectrum and move towards the harder more formalised end, if needed.

Other economies also have resources detailing their approaches to IRC:

Image Source: Pexels

Different forms of IRC

Image Source: Pexels

Unilateral action

Unilateral action could take many forms, including:

- Adopting similar regulatory settings to another economy or group of economies.

- Recognising the regulatory outcomes of another economy or group of economies, or

- drawing on evidence from another economy, group of economies, or international organisations to support domestic analysis and decision making.

Unilateral action is typically less burdensome than options such as seeking a common regulatory position. It can therefore be more easily used to reduce the impact of regulatory divergences. This form of cooperation can be characterised in different ways but is essentially about the actions that individual economies can take, without an expectation of reciprocity. This could include:

- Steps to integrate international considerations with domestic rulemaking processes. Examples could include: adopting international normative instruments, assessing trade impacts, involving foreign stakeholders, integrating an IRC focus into domestic strategies Mexico’s Regulatory Impact Analysis .

- Taking steps to unilaterally recognise the regulatory outcomes of another economy or group of economies as equivalent to that economy’s domestic outcomes NZ space activities case study.

- Taking steps to unilaterally adopt the same regulatory settings as another economy or group of economies NZ-Australia competition case study.

- The New Zealand IRC toolkit refers to the benefits and risks of unilateral action.

Information exchange/ information cooperation

The OECD sees this as a necessary first step and the foundation of all the cooperative approaches. It also features in the cooperation spectrum under informal cooperation (see below). The OECD describes this as comprising both informal and formal modes of engagement. It may be underpinned by supporting arrangements, but this is not essential.

Exchanging information has an important role in building common frameworks that improve understanding. The OECD work identifies multilateral platforms, through International Organisations, that support engagement and information exchange.

International capacity building is an important vehicle for information exchange. This can also lead to other two/way forms of cooperation such as common guidelines or standards.

Please refer to the case study: International Cooperation in Competition Law Enforcement

Image Source: OECD

Image Source: Pexels

Informal or soft cooperation

This is a flexible and non-binding form of cooperation, which features on the cooperation spectrum. It can take the form of policy coordination, information exchange, capacity building and the like between two or more economies. The main advantages of informal cooperation are that it:

- Tends to be lower cost to implement and maintain.

- Enables economies and regulators to build trust and confidence, making further deeper cooperation more likely.

- Preserves the ability of participants to leave the arrangement easily or the flexibility to change it.

- Allows one economy to change its policy and regulatory settings without reference to the other.

- May create efficiency gains from sharing resources.

- Creates opportunities for mutual learning.

Downsides of this option, when undertaken bilaterally or among smaller groupings of economies, can include that it is:

- Not as durable as formal arrangements, placing emphasis on goodwill, continued buy-in, and maintaining relationships.

- Achieves some, but generally not full, mutuality in approach.

Informal cooperation can be useful in emerging and fast-paced areas, where the actors involved have diverse objectives and a common framework is yet to be established. For more information, see Informal cooperation.

Mutual recognition

This form of IRC features as a cooperative form of engagement in the OECD framework. It also features in the cooperation spectrum, under the umbrella of formal cooperation.

The primary benefit of mutual recognition is the reduction of duplication, without needing to agree on common rules or processes. It can occur bilaterally, plurilaterally or multilaterally. Mutual recognition allows economies to recognise each other’s laws and regulations or standards, or to accept regulatory outcomes such as lab testing, conformity assessment or enforcement processes from other economies, while maintaining their own laws, regulations and standards.

Recognition of another economy’s laws and regulations or standards works well where there are high levels of trust in each other’s institutions and regulatory decision-making capabilities. Recognition of regulatory outcomes, particularly lab testing and conformity assessment, is more common and is typically used to support cross-border flows of goods.

The benefits from mutual recognition can include:

- Removing the cost for business of complying with two (or more) sets of regulatory requirements or standards

- Allowing economies to maintain their own regulatory settings and standards

- Providing a high level of certainty for firms operating in those markets

- Streamlining the administration of regulation

- Being a building block towards harmonisation.

It also has some potential downsides:

- It may only be viable where there is already a high level of convergence between the policy, regulatory settings or standards of participating economies.

- It may raise concerns about undercutting existing domestic settings, without a high level of trust and confidence in each other’s institutions and processes.

- It may require ongoing monitoring of each other’s regulatory regimes, in case substantive changes impact the basis on which mutual recognition has been agreed.

A 2016 OECD study focused on mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) found (FOOT NOTE), among other things, that MRAs are most feasible when regulatory divergences are not too high, and that they are more valuable for a few sectors with global value chains (see link to study below).

For more information on mutual recognition, see:

- Mutual recognition

- The OECD Environment, Health and Safety Programme – This is a longstanding cooperation platform that has increased efficacy and efficiency in OECD Members by improving implementation of chemicals management policies. A recent study found that the programme brings all participants savings of more than EUR 309 million. This comes, among other things, from harmonising industry dossiers of product registration, and reducing testing for new industrial chemicals.

- Correia de Brito, A., C. Kauffmann and J. Pelkmans (2016), “The contribution of mutual recognition to international regulatory co-operation”, OECD Regulatory Policy Working Papers, No. 2OECD Regulatory Policy Working Paper

- OECD Mutual Acceptance of Data for Chemicals

Image Source: Pexels

Image Source: Pexels

Enforcement Cooperation

This type of cooperation deals with the enforcement of rules and standards. Cooperation may take the form of an agreement between governments or regulators on regulatory enforcement activities such as evidence collection and investigation, enforcement action, and information sharing such as alerts on emerging compliance issues. There may also be informal arrangements to support technical assistance and general information exchange.

Cooperation on enforcement can deliver benefits including:

- Reducing non-compliance and incentives for businesses to put themselves beyond the reach of domestic regulators.

- Helping with the effective enforcement of domestic regulation where actions, actors or key information is overseas.

Potential issues with enforcement cooperation include:

- Legislative authority may be required before a domestic regulator can help an overseas regulator.

- Additional resources may be required to provide assistance to other regulators and ensure effective enforcement.

For more information, see:

Harmonisation

Both the OECD’s analysis and the New Zealand cooperation spectrum identify harmonisation as the most comprehensive form of IRC available to economies.

Harmonisation can be a good option between economies that share policy objectives or where a common approach makes sense. If regulatory approaches are similar to begin with, it can be easier to develop a common approach which works for the economies involved. These arrangements tend to be supported by a formal, legally binding agreement. They may be bilateral or plurilateral.

Rules developed by an international organisation, often supported by a formal international instrument or model law, will, if adopted by economies, result in a harmonised regime. These are often multilateral in nature.

The benefits of harmonisation include:

- Providing a high level of certainty and reduction of costs for businesses and the public operating across different economies, as well as increased compliance.

- Improving the quality of policy, regulation and standards through access to a wider pool of expertise and greater resourcing.

Harmonisation also has some potential downsides, such as that it:

- May be highly resource intensive and time-consuming to set up and maintain, which may, in some cases, be disproportionate to the nature of the issue to be addressed.

- Limits the ability of individual economies to determine their own policy and regulatory settings.

For more information see:

Image Source: APEC Secretariat

Image Source: Pexels

Regulatory Partnerships

The OECD Best Practice Principles identify the role of regulatory partnerships as a way of supporting economies to effectively cooperate across a variety of regulatory areas.

These may be quite formal in their structure and arrangements, such as the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council, which is backed by a Memorandum of Understanding. The Council, established in 2011, provides a forum for stakeholders to discuss regulatory barriers to cross border trade and investment, and identify opportunities for alignment and cooperation. See here. for more information.

In other cases, there may be levels of engagement from the highest political level down to further shared economic and regulatory integration goals. This is the case for Australia and New Zealand in relation to the Single Economic Market agenda [See Box 5.10].

The Pacific Alliance has a Technical Group on Technical Barriers to Trade Regulatory Cooperation.

International Organisations

International organisations provide the institutional setting and technical expertise to drive international regulatory cooperation. They have been doing so for decades, resulting in the development of instruments, either legally binding or soft law, across a range of topics.

Economies can participate in these international fora, contributing to the development of international instruments (both binding and non-binding), and facilitate the domestic adoption of these instruments.

International organisations vary in their nature, mandate and membership. They may have different forms, including multilateral, regional and groups of like-minded institutions or officials in specific sectors (such as trans-governmental networks of regulators).

APEC and the OECD are international organisations that have been active in the development of international regulatory cooperation initiatives of varying kinds for their members.

Image Source: New Zealand MBIE Trade and International Team